In recent years, the rapid decline in the cost of next-generation sequencing (NGS) and increasing the length of readable sequences have led to the development of two shotgun sequencing and 16S rRNA gene profiling approaches to describe the structure of microbial communities. These approaches could become standard tools for scientists and many laboratories in the field of microbial ecology in the near future. Then shotgun sequencing, 16S rRNA sequencing is more economical. Therefore it is frequently used for studies with large sample sizes or time series, however, it cannot give insight into the metabolic structure of microbial communities.

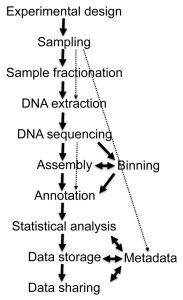

Figure 1. Different stages of metagenome projects. Metagenomics – a guide from sampling to data analysis; Torsten Thomas et al. 2012.

The use of 16S rRNA sequencing back to the 1980s, when a new standard for identifying bacteria was first developed. It is then discovered that the phylogenetic relationships of bacteria and all biological organisms could be determined by comparing the stable part of the genetic code. In bacteria, these genetic regions included the genes encoding the 16S, the 5S, the 23S, and the regions between these genes. Today, the 16S rRNA gene is mostly used in bacteria for taxonomic targets. The 16S rRNA gene is a vital part of cell function, a target for antimicrobial agents, and composed of conserved and 9 highly variable regions that have different position, length, and taxonomic differentiation. The approximate length of the 16S rRNA gene is about 1550 bp. Comparison of 16S gene sequences in all major phyla of bacteria makes it possible to differentiate between them at the genus level. In addition, differences in the hypervariable region of ribosomal RNA genes are ideal for phylogenetic studies. The hypervariable region 4 (V4) amongst the short regions (<300 bp), is usually the most usable. 16S rRNA sequencing is an amplicon-based and vigorous tool that is widely used for metagenomic studies. The identification of microbial communities based on phenotypic characteristics is not as accurate as genotypic identification methods. Rarely isolated and poorly described strains, novel pathogens, mycobacteria and no cultured bacteria can be better identify by 16S rRNA gene analysis. This feature can have a significant impact on patient identification and care and also led to improved clinical results and provide exactly grouped organisms for more studies. 16S rRNA gene sequencing is currently the most accurate method for identifying microbial communities in various biological samples. One of the most important applications of the 16S rRNA sequencing method is the identification of unknown organisms based on previous knowledge and it can be said that it is the best choice in this field.

Despite all these advantages, there are problems such as inaccuracy of sequences in some databases, the proliferation of species names based on minimal phenotypic and genetic differences, microheterogeneity in 16S rRNA sequences within a species, and finally, lack of quantitative definition of genus or species based on 16S rRNA data. The most important challenge is the extraction of biochemical signaling pathways from 16S rRNA data that can be used in smaller clinical laboratories.

Necessity of 16S rRNA databases

In general, the existence of databases with accurate biochemical and morphological descriptions of strains is essential for the phenotypic identification of microorganisms. In parallel, in order to accurately identify the 16S rRNA gene sequences of microorganisms, it is necessary to have databases containing a collection of exact sequences with appropriate names with these sequences and exact sequences for isolated types. databases such as GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), MicroSeq, the Ribosomal Database Project (RDP-II) (http://rdp.cme.msu.edu/html/), Smart Gene IDNS (http://www.smartgene.ch), the Ribosomal Database Project European Molecular Biology Laboratory (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/embl/), and Ribosomal Differentiation of Medical Microorganisms (RIDOM) (http://www.ridom.com/) are examples of associated databases.

Figure2. Universal phylogenetic tree based on the 16S rRNA gene sequence comparisons. Pace, N. A molecular view of microbial diversity and the biosphere. Science276:734-740. 1997.

References

- A comprehensive benchmarking study of protocols and sequencing platforms for 16S rRNA community profiling.

- Community genomic and proteomic analyses of chemoautotrophic iron-oxidizing “Leptospirillum rubarum” (Group II) and “ Leptospirillum ferrodiazotrophum” (Group III) bacteria in acid mine drainage biofilms.

- Metagenomics – a guide from sampling to data analysis.

- Tax4Fun: predicting functional profiles from metagenomic 16S rRNA data.

- Impact of 16S rRNA Gene Sequence Analysis for Identification of Bacteria on Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases

- Bottger, E. C.1989. Rapid determination of bacterial ribosomal RNA sequences by direct sequencing of enzymatically amplified DNA. FEMS Microbiol. Lett.65:171-176.

- Garrity, G. M., and J. G. Holt.2001. The road map to the manual, p. 119-166. In G. M. Garrity (ed), Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology. Springer-Verlag, New York, N.Y.

- Harmsen, D., and H. Karch.2004. 16S rDNA for diagnosing pathogens: a living tree. ASM News70:19-24.

- Kolbert, C. P. and D. H. Persing.1999. Ribosomal DNA sequencing as a tool for identification of bacterial pathogens. Curr. Opin. Microbiol.2:299-305.

- Tortoli, E.2003. Impact of genotypic studies on mycobacterial taxonomy: the new mycobacteria of the 1990s. Clin. Microbiol. Rev.16:319-354.

- Drancourt, M., C. Bollet, A. Carlioz, R. Martelin, J. P. Gayral, and D. Raoult.2000. 16S ribosomal DNA sequence analysis of a large collection of environmental and clinical unidentifiable bacterial isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol.38:3623-3630.

- Pace, N. A molecular view of microbial diversity and the biosphere. Science276:734-740. 1997.

prepared by: Parvin Zarei