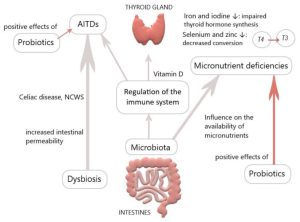

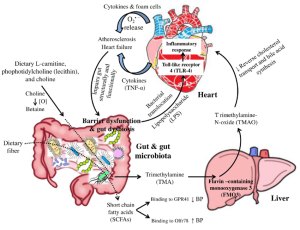

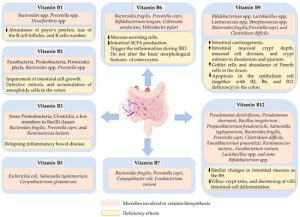

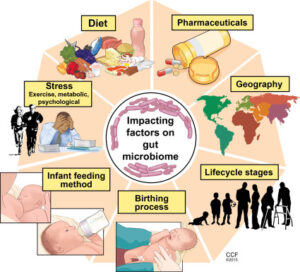

The gut microbiota plays a pivotal role in thyroid disorders, including Hashimoto thyroiditis, Graves’ disease and thyroid cancer. Recent data have suggested that microbes influence thyroid hormone levels through the regulation of iodine uptake, degradation, and enterohepatic cycling.

Studies have been shown that Lactobacillaceae and Bifidobacteriaceae are often reduced in hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism. In Graves’ disease patients, the composition of the gut microbiota differs from that of healthy individuals, with a significant decrease in the relative abundance of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Butyricimonas faecalis, Bifidobacterium adolescentis and Akkermansia muciniphila compared to the control. Furthermore, a diagnostic model was developed using metagenome-assembled genomes of the gut microbiome, which may serve as a valuable predictor for Graves’ disease. The gut microbiota has the capacity to produce various neurotransmitters, such as dopamine, which can regulate the hypothalamus-pituitary axis and inhibit thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH).

The Effects of Probiotics and prebiotics on thyroid function

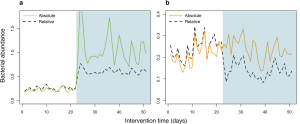

Numerous studies have been conducted to investigate the modulation of gut microbiota in order to restore dysbiosis in patients with thyroid disorders. Probiotics and prebiotics have demonstrated beneficial effects on thyroid diseases. Probiotics including bifidobacterium longum supplied with methimazole was implemented in nine patients with Graves’ disease for six months. The results showed a significant reduction in clinical thyroid indexes, including free T3, free T4, and thyrotropin receptor antibody (TRAb), while TSH levels increased compared to baseline. Another study explored the effects of a four-week treatment with a complex probiotics preparation consisting of Bifidobacterium infantis, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Enterococcus faecalis and Bacillus cereus in patients post-thyroid hormone withdrawal (THW) following thyroid cancer surgery. The treatment led to a decreased occurrence of complications such as dyslipidemia and constipation. However, the serum levels of free T4, free T3 and TSH showed no change between groups. Synbiotics, which are a mixture of probiotics and prebiotics, have also been examined. They have shown potential in reducing TSH and increasing freeT3 in patients with hypothyroidism. A strategy based on microbiome-directed therapies, involving supplementation with probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics holds promise as a therapeutic approach for thyroid disorders.

Conclusion

There is a growing interest in investigating the potential role of probiotics or prebiotics supplementation to improve thyroid function in humans. A recent meta-analysis indicates that supplementation with probiotics/prebiotics has no significant effect on thyroid hormone levels, while showing a modest decrease in TRAb levels. However, the results have been inconsistent, and the probiotics or prebiotics are various in each randomized clinical trial, leading a mixed effect.

References

- Shu Q, Kang C, Li J, Hou Z, Xiong M, Wang X, and Peng H. Effect of probiotics or prebiotics on thyroid function: A meta-analysis of eight randomized controlled trials. Plos one. 2024 Jan 11; 19(1):e0296733.

- Lin B, Zhao F, Liu Y, Wu X, Feng J, Jin X, et al. Randomized Clinical Trial: Probiotics Alleviated Oral-Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis and Thyroid Hormone Withdrawal-Related Complications in Thyroid Cancer Patients Before Radioiodine Therapy Following Thyroidectomy. Frontiers in endocrinology. 2022; 13:834674.

- Talebi S, Karimifar M, Heidari Z, Mohammadi H, Askari G. The effects of synbiotic supplementation on thyroid function and inflammation in hypothyroid patients: A randomized, double‑blind, placebo‑controlled trial. Complement Ther Med. 2020; 48:102234.

Provided by: Dr. Nazila Kassaian